Judith Kerr and the British

Author

,Berlin

,Stole the Rabbit

,Survivor

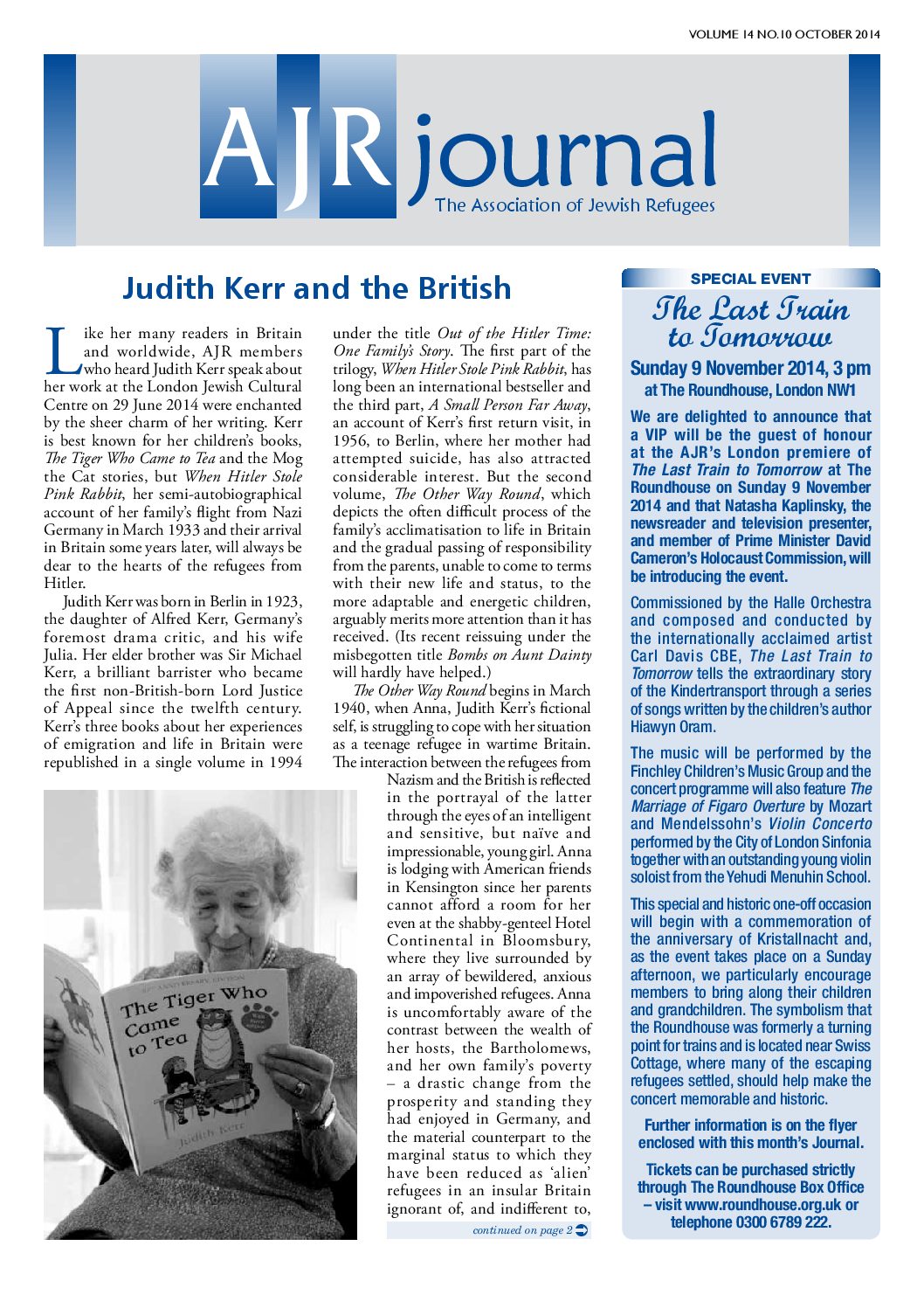

Like her many readers in Britain and worldwide, AJR members who heard Judith Kerr speak about her work at the London Jewish Cultural Centre on 29 June 2014 were enchanted by the sheer charm of her writing. Kerr is best known for her children’s books, The Tiger Who Came to Tea and the Mog the Cat stories, but When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit, her semi-autobiographical account of her family’s flight from Nazi Germany in March 1933 and their arrival in Britain some years later, will always be dear to the hearts of the refugees from Hitler. Judith Kerr was born in Berlin in 1923, the daughter of Alfred Kerr, Germany’s foremost drama critic, and his wife Julia. Her elder brother was Sir Michael Kerr, a brilliant barrister who became the first non-British-born Lord Justice of Appeal since the twelfth century. Kerr’s three books about her experiences of emigration and life in Britain were republished in a single volume in 1994 under the title Out of the Hitler Time: One Family’s Story. The first part of the trilogy, When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit, has long been an international bestseller and the third part, A Small Person Far Away, an account of Kerr’s first return visit, in 1956, to Berlin, where her mother had attempted suicide, has also attracted considerable interest. But the second volume, The Other Way Round, which depicts the often difficult process of the family’s acclimatisation to life in Britain and the gradual passing of responsibility from the parents, unable to come to terms with their new life and status, to the more adaptable and energetic children, arguably merits more attention than it has received. (Its recent reissuing under the misbegotten title Bombs on Aunt Dainty will hardly have helped.) The Other Way Round begins in March 1940, when Anna, Judith Kerr’s fictional self, is struggling to cope with her situation as a teenage refugee in wartime Britain. The interaction between the refugees from Nazism and the British is reflected in the portrayal of the latter through the eyes of an intelligent and sensitive, but naïve and impressionable, young girl. Anna is lodging with American friends in Kensington since her parents cannot afford a room for her even at the shabby-genteel Hotel Continental in Bloomsbury, where they live surrounded by an array of bewildered, anxious and impoverished refugees. Anna is uncomfortably aware of the contrast between the wealth of her hosts, the Bartholomews, and her own family’s poverty – a drastic change from the prosperity and standing they had enjoyed in Germany, and the material counterpart to the marginal status to which they have been reduced as ‘alien’ refugees in an insular Britain ignorant of, and indifferent to, the hardships experienced by those forced to flee the Nazi dictatorship. Anna’s first impressions of Britain, conveyed in the final pages of When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit, are predominantly favourable: after the open hostility displayed by their Parisian concierge towards the family both as refugees and as Jews, Britain appears reassuring, if unfamiliar. The weather that greets them on their crossing from France may be appalling but in Newhaven a ‘kind but incomprehensible’ porter puts them on the right train to London. The English passengers may sit bolt upright behind their newspapers, barely exchanging a word, but on alighting from the train they form an orderly queue to leave the platform, with none of the pushing and jostling customary in Continental countries. The language may at first be incomprehensible: the children are puzzled that every station appears to be called ‘Bovril’, until their mother informs them that this is ‘some kind of English food’, eaten, she thinks, with stewed fruit. And though at Victoria Station Anna and her brother Max are initially baffled by a porter’s enquiry ‘Ittla?’, they rapidly understand his meaning when he places his fingers moustache-like under his nose, mimes a Nazi salute, then spits forcefully (and to them reassuringly) onto the platform. When The Other Way Round begins, in 1940, Anna has experienced life in Britain, with its attendant hardships and humiliations, as a refugee for some four years. Since her parents can no longer pay for her hotel room she has ‘become like a parcel, to be tossed about, handed from one person to another, without knowing who would be holding her next’, a metaphor that strikingly conveys the insecurity of the child refugee’s life. She had first been taken in at the Metcalfe Boarding School for Girls, where she, ‘the clever little refugee girl’, had not fitted in among the beefy, hockey-playing English pupils. As the opening paragraphs of the book show, life with the Bartholomews is more pleasant, but no less demeaning, in that she is constantly conscious of living on her hosts’ charity: she is reduced to wearing the slightly shabby clothes handed down to her by the Bartholomews’ daughters and her handbag is a cast-off of her mother’s from Berlin. But, apart from these signs of poverty, Anna has become almost indistinguishable from other middle-class English girls after four years of life and schooling in Britain. She and Max have come to feel themselves in large measure British, or at least the equals of their British counterparts, and are intensely resentful and indignant when they are considered inferior on account of their status as ‘alien’ refugees or are singled out for treatment different to that accorded their British peers. Travelling to Cambridge to spend a weekend with Max, who is studying there, Anna’s external appearance is that of a British girl of her age but in matters other than clothing the sense of otherness persists, most importantly in the way that she is perceived as different, both by others and by herself. On the train to Cambridge, she encounters a ‘tweedy woman’, the archetypal middle-class English lady. At first, the lady takes Anna for an English girl going to Cambridge for social purposes befitting someone of her class and befriends her. But she is disconcerted to learn that Anna comes from Berlin: ‘I should never have thought it. You haven’t got a trace of an accent. I could have sworn that you were just a nice, ordinary English gel.’ The idea that Anna is from Germany but opposed to her native country in time of war is too much for the tweedy lady, who, offended by what she considers a deception practised on her, buries herself reproachfully in Country Life. Only a slow process of immersion in British life during the war leads Anna to feel, by the time of the VE Day celebrations in May 1945, that she belongs in her adopted homeland. Even more than Anna, Max is desperate to be taken for English. He adapts with astonishing speed to the British educational system; his academic gifts rapidly gain him a scholarship to Cambridge, where his sister is amazed to see him behaving exactly like an English undergraduate, and being treated as such by his English friends. Hence his fury and dismay when, a short time later, he is interned as an ‘enemy alien’. Max suffers no particular ill treatment and is indeed released from internment unusually early: ‘But he clearly hated it. He hated being imprisoned and he hated being treated as an enemy, and most of all he hated being forced back into some kind of German identity which he had long discarded.’ After his release, Max is determined to prove his Britishness to the British: overcoming all obstacles, he succeeds in joining the RAF and, when Bomber Command and Fighter Command refuse to allow him to fly on operations on the grounds that he cannot be allowed to fly over German territory, he persuades Coastal Command to accept him, arguing that no rule prevents him from flying over the sea. By the end of the book, as he walks through the London crowds on VE Day in RAF uniform, the salutes he receives signal his acceptance as a respected member of the national community. The image of Britain as a country of refuge also changes markedly in the course of the narrative. At first, much of the emphasis is on the failure of the British to understand the position of the Jews driven out of Germany by the Nazis, on the shabby poverty they endure and on the frustration of successful and educated people forced into inactivity or, at best, into menial jobs. However, the Kerrs come to admire the behaviour of the British in wartime, the tenacity of their resistance to the Nazi juggernaut and their stolid resilience during the Blitz. The spirit of solidarity that unites the civilian population embraces even the refugees at the Hotel Continental as they listen exultantly to the BBC radio news announcing the losses suffered by the Luftwaffe on 15 September 1940, the crucial day in the Battle of Britain. By the end of the book, in 1945, the Kerrs also feel a modest pride in being part of the community that has won so hard-fought a victory. Anthony Grenville